Context

The severity and near-apocalyptic nature of this present-day Haitian crisis, wrought by corrupt Haitian politicians and an anti-nationalist oligarchy, has brought a sense of hopelessness and a psychosis of fear within the population akin to the darkest days of the Duvalier dictatorship regime.

In Haiti today, kidnappings, murders, collective rapes, resurgence of cholera, 39% inflation, school and factory closings and -according to the latest United Nations report- regional famine affecting more than 4.5 million Haitians, are prevailing in a leaderless society. The same report warns of spike in gang attacks: “gross human rights abuses in Haiti. Extreme violence and gross human rights abuses, including mass incidents of murder and sniper attacks, have sharply increased in Cité Soleil on the outskirts of the Haitian capital.”

The Underlying Factors of Insecurity in Haiti

Because of the armed gangs, fear has settled in people’s heads, because each day brings its share of kidnappings or murders. Insecurity is in full swing and, in the capital as in other Haitian cities, the war for territorial control is bloody. But where do these gangs come from?

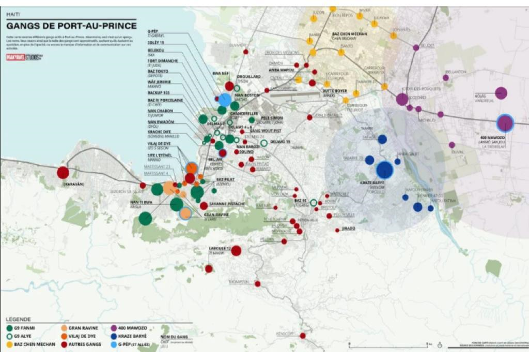

In Haiti, armed gangs and insecurity go hand in hand and constitute a disturbing social phenomenon, especially in the capital where no less than 96 gangs operate, according to the National Commission for Disarmament, Dismantling and Reintegration.

These armed gangs create and fuel insecurity in a country that already has a long history in this area. Several studies attempt to explain the origin of these sometimes ultra-violent gangs and the links that unite them to political and economic powers and NGOs.

It is impossible to talk about the social, economic and political situation in Haiti without addressing the issue of gangs and armed groups. At least that’s what Athena R. Kolbe, a professor at the University of North Carolina, who conducts field research in Haiti on gangs and armed groups, believes.

“Armed groups, urban or rural, have a great influence on democracy in Haiti,” she said. They are so established in Haitian society that no one can really run a business, or organize large-scale activities in the country, without at some point or another coming into contact with them. »

The researcher, however, draws a distinction between armed group and gang. “Not all gangs are armed and not all armed groups are gangs,” she adds. There are still small, unarmed gangs in some neighborhoods that have not affiliated with larger groups. And in the armed groups, there are certainly gangs, but also private militias, criminal syndicates and political groups. »

The links between politics and banditry have always been known, even if, according to Athena Kolbe, we prefer not to talk about it. But for the researcher, when the state fails in its mission to serve citizens, gangs can easily form and take their place.

As it is with the gangs, armed groups tend to be highly politicized, she said. The case of the former Haiti Armed Forces (FADH) of Haiti is emblematic, but there are other examples. And the international community would have its own way of seeing these different groups of armed men, more or less violent.

“One of the mistakes of the United Nations intervention in Haiti in 2004 was not to have seen the difference between armed groups,” she said. The UN has invested a lot of money in dismantling urban gangs. But she did not understand that the ex-FADH had their own armed groups, which would later also engage in criminal actions. Foreign powers have political interests in labeling one group as evil, and another as good, when in reality those who join these two groups look alike. » At best, separating armed groups from gangs is an erroneous proposition.

From Brigades to Gangs

The origin of armed groups, especially gangs, is diverse, according to the researchers. For Roberson Édouard, some gangs originate from a distorted need for security. “After the departure of Jean Claude Duvalier, there was a social demand for security at all levels, explains the sociologist. But the state has failed to meet this need. Citizens then had to provide this security themselves. »

It was the brigades, now mostly gangs, that turned against the citizens they were meant to protect in the first place.

Strong links with politics

This explanation is not the only one. Jean Rebel Dorcenat, spokesperson for Haiti’s National Commission for Disarmament, Dismantling and Reintegration, said in an interview with journalist Samuel Celiné that elected politicians are often behind the distribution of weapons, to control their constituencies for example.

The example of president Jean Bertrand Aristide is revealing of this invisible hand. According to David Becker, who worked for USAID as an expert on security issues in Haiti and who is quoted in an article by the National Defense University, Aristide had provided weapons in large numbers to young people, in exchange for their support. These weapons have also given groups the opportunity to engage in violent actions and crimes. After the departure of Aristide, driven out by armed groups, the “asayan” -these gangs involved in various crimes- increased their control in their areas of influence.

Oliver Djems thinks that the “ chimeres ” (names given to armed Aristide’s supporters) of the 2000s have mostly turned into gangs. “ The story of the gangs of Port-au-Prince is that of a transformation of chimeres, who then became gangsterized ”, he explains.

When the lines are blurred Between these armed groups and the population, the relationship is not always clear. The gangs especially, closer to the inhabitants, because they come from the same marginalized communities, have developed over time strategies that bring them closer to the latter.

According to Athena Kolbe, gangs are often considered in these territories as political associations, sorts of community groups called baz (base) in Creole. “Those who lead the gang are most often children from the area controlled by the gang,” explains the researcher. But now it’s not those rambunctious young people who roamed the streets. They are armed, and can steal and kill. However, they are also the ones who can protect the area, and even find work for the residents. These are complicated reports. »

For Olivier Djems, in these districts, there can be several chiefs who each delimit their territory. “Bandits are sometimes considered saviors, ‘good-hearted dads’,” says the sociologist and former journalist. I remember that when “Te Quiero”, a bandit from Cité Soleil, died, schools did not operate in the town on the day of his funeral. People were crying. »

The Strange Contribution of NGOs

January 2010 earthquake also played a major role in the development of gangs, especially those in the capital. “Gangs existed before the earthquake,” Kolbe said. But the disaster has upset the relationship between the gangs and their respective areas of influence. They were thus able to gain new territories. Some gangs got weaker, but others got stronger. »

Some international organizations, mostly NGOs, have even used these gangs to reach areas where they could not have entered without their help. This filled the coffers of these armed gangs which, suddenly, became providers of employment.

In her study, Athena Kolbe reports the case of a gang that applied for international funds. He received $50,000 from charity. A cash for work program was able to be set up by this gang, in the community it controlled.

Olivier Djems confirms that gangs thrive thanks to the actions of certain NGOs. “In the same neighborhood, there may be several NGOs providing the same services,” he says. In general, the presence of these NGOs promotes the creation of grassroots community associations. But at the same time, the NGO is forced to come to terms with the neighborhood chief, who is often a bandit. Thus, someone else in the neighborhood may seek to create his own gang, to also benefit from the favors of the NGOs. »

But some NGOs have also contributed to the decline in violence in neighborhoods, such as Bel-Air. “Around 2005, the NGO Viva Rio organized a series of meetings between gang leaders, explains Athena Kolbe. Within a few years, the NGO finally convinced everyone, including the police, not to attack each other anymore. »

The monetary cost of this ceasefire was, however, quite high. “Each month that there had been no murders, continues Kolbe, there were gifts for all parties to the agreement, including the police. These included, for example, scholarships for neighborhood children. But it is difficult to maintain such an agreement, even if it is successful. It takes social workers, community liaisons, constant funding, etc. “.

Other approaches have been used to undermine gang influence. One of them was to create NGOs offering the same services in the communities where they reigned supreme. “Let’s take a neighborhood where the authorities do not collect garbage,” explains Athena Kolbe. The gang that controls the area may decide to take care of it, buy equipment and hire people from their locality to pick it up. The idea then is to set up an organization that does what the gang wants to do. She receives funds and hires people from the area for the collection. The idea is to marginalize the gang in this way. But it is an approach that has not been successful because in the end, the NGO’s money will dry up while the gang is still there. »

The Instigator State

Between the state and armed groups, particularly gangs, the relationship is not always one of hatred. In June 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, a coalition of gangs was created in the Haitian capital. Before this strange grouping, called G9, each of the gangs was stirring up trouble in its area of influence, sometimes attacking new territories.

The G9, federating nine gangs in the metropolitan area, is an emanation of power, according to reports from human rights organizations. For Athena Kolbe, nothing surprising in the formation of this coalition, which however worries her for the future. “Gangs have operated in Haiti in a similar way since 1980,” says the researcher. There have always been formal and informal alliances between them. Around 2002 and 2003, there were alliances between certain gangs and rebels and militias who wanted to overthrow the government. But when gangs that are more driven by crime than politics combine forces, it’s very scary. »

Yet political issues would be central to the formation of the G9. After various massacres in working-class neighborhoods such as La Saline or Bel-Air, where the majority of opponents to power reside, some believe that this coalition of armed groups would aim to facilitate victory in the next elections for the party of the current President Jovenel Moise.

Indeed, the electoral weight of the neighborhoods targeted by the g9 gangs is not at all negligible. All reports by human rights organizations denounce connivance between the state and armed bandits. Even if in recent times, acts of clear distancing have been taken, such as large-scale police operations in Grand Ravine, doubt still remains as to the motivations of the “ soldiers ” of Jimmy Cherizier and his acolytes.

The Recent History of Gangs in Haiti

1- First failed coup attempt to overthrow Duvalier,1 led by military officers and foreigners. 1958 1959Duvalier creates paramilitary force known as the Tonton Macoute to serve as a counterweight to the army.2 The ‘Macoute’ becomes main domestic security force.3 Macoutes are known to carry out massacres, assassinations and political violence on behalf of the regime over decades.

2- 1971–1986: JEAN-CLAUDE DUVALIER Duvalier appoints his son, Jean-Claude Duvalier, as president before he dies.4 1971Jean-Claude Duvalier renames Tonton Macoute as the Volunteers for National Security (MVSN).5 After two months of violent demonstrations against his 14 years of heavy-handed rule, Jean-Claude Duvalier flees to France.6 1986

3- 1986–1988: NATIONAL COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENT Military regime: An army-led interim government, the National Council of Government (CNG), is established, led by General Henri Namphy. Legislative Chamber and Duvalier’s armed forces, MVSN, are dissolved.7 1986 MVSN officially disbanded by government. Never disarmed, they continue to operate for many years on informal basis.8 People celebrating end of Duvalier regime killed by army in multiple instances, including nearly 100 people in Léogane (south-west of Port-au-Prince) and FortDimanche massacre. February: People take to the streets of Port-au-Prince, attacking the Macoute militias, stoning and burning alive their targets, and destroying the symbols of the regime. Most victims are low-level leaders and religious leaders affiliated with the Macoute.

4- 1986–1988 Civil unrest: Street protests, labour movement strikes against CNG, popular uprisings in regions (Gonaives).9 Voters approve a new constitution banning dual citizenship and restricting Haitian Americans from running for president in Haiti. The constitution is ratified in March 1987, but only fully reinstated in October 1994.10 1987Late 1980s to early 1990s: The Macoute re-emerge as a pro-government armed group working with various administrations.11 Political violence continues. In 1987, army kills 22 striking dockworkers in the port of Port-au-Prince and at least 139 peasants in Jean-Rabel (North-West department) by paramilitaries acting on behalf of local landowner. Namphy declares martial law. Attacks on political leaders, church workers and peasant organizers intensify.

1988 September: Massacre of Saint-Jean Bosco – armed men, likely former Macoutes, kill at least 13 people (and injure 80) in the church of Saint-Jean Bosco, Portau-Prince. The church was the parish of the priest and future president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, an opponent of Duvalierism and the military regimes.

5- 1988–1990: PROSPER AVRIL General Prosper Avril, former head of the Duvaliers’ presidential guard, overthrows General Namphy in a coup.13 SEPTEMBER 1988 Avril resigns amid protests. Hérard Abraham remains in power for three days, surrenders voluntarily to establish a new provisional government and prepare for elections.14 MARCH 199012 March: The Massacre of Piatre – in the villages of Piatre, Déjean, Dupervil, Ka Jan and Ti Plas, soldiers and armed civilians from Saint-Marc kill 11 peasants in a land dispute between peasants and landowners.

6- FEBRUARY 1991–SEPT 1991: JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE Jean-Bertrand Aristide becomes the first president not-aligned to Duvalier. René Préval becomes his prime minister. 1991September: SSP militia emerges when Aristide allegedly allows General Cédras to form a private militia, which then deposes Aristide in a coup. Aristide flees the country. SSP said to dissolve after coup.

7- 1991September: SSP militia emerges when Aristide allegedly allows General Cédras to form a private militia, which then deposes Aristide in a coup. Aristide flees the country. SSP said to dissolve after coup. Political eventRegime/dateGangs, non-state armed groups, political violence SEPTEMBER

8- 1991–1994: RAOUL CÉDRAS 1991 Following the coup, several paramilitary groups form to support the military regime of Cédras. Former Macoutes reassemble as ‘attachés’, or vigilantes connected to government security forces, such as Capois La Mort. This includes small paramilitary groups formed by former Macoutes. Two to three weeks of attacks by soldiers, former Macoutes and various armed groups on members of the democratic movement, including supporters of President Aristide, Lavalas leaders and civil society organizations. September: UN Security Council establishes the UN Mission in Haiti (UNMIH). 1993 FRAPH (Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti), a far-right paramilitary group, emerges to prop up Cédras regime and counteract support for deposed President Aristide. It includes former Macoutes.18 1993–1994Multiple massacres carried out by the FRAPH, military and paramilitary groups, including the Carrefour Vincent Massacre and Raboteau Massacre.

9- 1994–1996: JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE Aristide returns to power with help from multinational forces. Haiti’s National Assembly creates new civilian law enforcement, with the Haitian National Police and the Haitian Coast Guard, with the help of US and UN.19 1994 –1995Aristide outlaws paramilitary groups and disbands the military. The decommissioning of Haitian Armed Forces (FAd’H) leadership in 1994 sees the military evolve into an illicit power structure, with support in the northern and central provinces. Government’s lack of action on issues of military pensions and retraining for unemployed soldiers cause more to join armed groups.

10- From 1995 to 2006, President Aristide created a criminal network in the form of gangs protected by government officials, notably his head of security at the Palace, Oriel Jean, Interior Ministers Mondesir Beaubrun and Jocelerme Privert, several chiefs and the national police, Fourrel Celestin, Jean Claude Jean Baptiste, Nesly Lucien, Hermionne Leonard ROudy Therassan, Marcellus Camille, Romain Wisler. This criminal network received direct instructions from Aristide. The network was responsible for political assassinations, kidnappings, robberies, rapes, drug trafficking and corruption. Independent gang structures operated on his orders. The best known are Lame ti manchet, rat blade, cannibal blade, wouj blade, Domi nan Bwa, Bale Douze etc. Gang leaders had direct access.

This sound General Titi, Yves Oiseau alias Robenson Thomas alias Labanyè and his assistant kolibri was the chef la Baz boston. Amaral Duclona was the head of Baz Belekou in Cite Soleil 19. Emmanuel Vilme responsible for the assassination of Dr. Ary Bordes, head of Baz Bois neuf.

11- 1996–2001: RENÉ PRÉVAL.- Préval is elected president and begins to implement structural reforms and privatization. He rules by decree, dismisses legislators, and local elected officials are converted into state employees in 1999. Neoliberal reforms are the basic policy disagreement between Préval supporters and Fanmi Lavalas (Aristide’s party) but support for Aristide (or lack of) dominates the debate. 1996 May: Parliamentary, provincial and municipal elections take place supervised by the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP). There are no substantive boycotts and voter turnout is more than 60%. Fanmi Lavalas dominates the results with a new right-wing, Protestant Party being the only other group to record significant national support. 2000Early 2000s: Aristide forms his own armed gangs known as the Chimères (operating in concert with the police and as protection rackets). The pro-Aristide group is mainly used as an instrument of political opposition23 in exchange for power and patronage.

12- 2001–2004: JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE Aristide is sworn in again as president.252001New moves by government to disarm militias and crack down on ex-soldiers begin. 2003–2004Armed group National Revolutionary Front for the Liberation and Reconstruction of Haiti forms as an alliance between two elements opposed to Aristide: armed anti-government gangs and former soldiers of the disbanded Haitian army.26 February 2004: The Cannibal Army, aka Artibonite Resistance Front, seizes control of Gonaives from government. This triggers the 2004 coup, which leads to Aristide’s departure.

13- Political eventRegime/dateGangs, non-state armed groups, political violence Aristide flees to the Central African Republic, claiming to the media he was kidnapped. His supporters denounce a coup. FEBRUARY 2004Following Aristide’s departure, the Chimères continue to operate in the Port-au-Prince basin carrying out kidnapping, assassinations and terror operations, notably Operation Baghdad.

14- 2004–2006: BONIFACE ALEXANDRE With no reference to the Haitian constitution, a ‘council of the wise’ is set up to select a new prime minister. Gérard Latortue is appointed.

MARCH 2004 – Paramilitaries retake control of the former Haitian army headquarters. Aristide’s supporters, and activists and officials are hunted down. One of the most prominent, Prime Minister Yvon Neptune, is unable to leave his office as his home is burned and looted.

2005The police deploy civilian vigilantes to carry out slum raids targeted the gangs supporting Aristide.Public support for the ex-military gangs fades as they fight the police, backed by the UN stabilization mission. UN peacekeeping mission increasingly confronts ex-soldiers, and pro- and anti-Aristide street gangs.

15- 2006–2011: RENÉ PRÉVAL Provisional Electoral Council bans 15 political parties from participating, including Famni Lavalas (Aristide’s party).

2010 During the second presidency of Préval, crime levels fall following his efforts to depoliticize and clean up the National Police. January: Earthquake hits Haiti with devasting impact. The earthquake leads to thousands of prisoners escaping from the National Penitentiary in Port-au-Prince. Many escaped gang leaders return to their original neighborhoods; others take over makeshift camps designed for earthquake victims. A new armed group, the Armée Fédérale, brings together escaped prisoners. The escapees use the camps as safe havens, and the police hesitate to enter in pursuit of criminals for fear of civilian casualties. Police concede they cannot address security in camps and encourage citizens in slums to deal with criminals themselves. Groups form night-watches and armed defense units. From 2010, older neighborhood self-defense groups, the “bases”, are overtaken by younger, less ideologically driven gangs after the earthquake; these new gangs are more disposed to challenge competing gangs. August: At least 20 candidates register to run for president in elections the government and UN remain committed to on 28 November.

2011Gender-based violence spreads in the camps. Rape, violence and child prostitution increase in the absence of security patrols and gang recruitment among unemployed youth.

16- 2011–2016: MICHEL JOSEPH MARTELLY Martelly wins 68% of the votes, in a very low turnout. Martelly founds Haitian Tèt Kale Party (PHTK).

MARCH 2011 Martelly announces a plan to reinstate the nation’s military. AUGUST 2011Ex-military gangs occupy former military posts and buildings before their formal reinstatement, asserting authority over the government. Elections take place with violence erupting, causing police to close a number of polling stations.

AUGUST 2015 Presidential elections held and Jovenel Moïse of the PHTK (Martelly’s choice) receives 32.8% in first round. OCTOBER 2015 2016400 Mawozo gang is created in the Croix des Bouquets neighbourhood of Port-au-Prince. It has been expanding significantly since 2018.41 November: Moïse is elected president with 55.7% of the vote.

17- 2017–2021: JOVENEL MOÏSE Moïse assumes presidency in February, announces reinstatement of the Haitian Armed Forces. PetroCaribe scandal: Special Haitian Senate Commission issues report on the management of a US$2 billion loan via Venezuela’s PetroCaribe oil programme, accusing former prime ministers and Moïse’s chief of staff of corruption and poor management. Opposition protests organized.45 MINUSTAH leaves Haiti.

2017Grand Ravine massacre: In November, 200 Haitian police raid the Grand Ravine area, in an anti-gang operation that ends up with the summary execution of innocent civilians on a school campus.47 Popular protests are triggered over the PetroCaribe scandal and continue through to 2020.

2018 Members of Moïse’s government allegedly assist in massacres by providing gangs with money, weapons, police uniforms and government vehicles used in attacks in Port-au-Prince, including La Saline.48 UN Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) established.

2019 – 2020 – G9 and Family (G9 An Fanmi) forms as a criminal federation of nine of the most powerful gangs in Port-au-Prince. The G-Pèp emerges as an alliance of gangs in Cité Soleil, allied with other armed groups around the capital, in opposition to G9.

APRIL–MAY 2021 Clashes between rival gangs erupt in the urban areas of Martissant, Fontamara and Delmas, leading to hundreds of houses being burned down or damaged, causing a wave of evacuees.51 Moïse assassinated by a team of foreign mercenaries. Murder remains unsolved. Claude Joseph, interim prime minister, declares himself in charge and imposes 15 days of martial law.

JULY 2021 – Jimmy Chérizier holds a press conference and pushes for protests against the assassination, accusing opposition leaders and the police of being behind the killing.

18- 2021–PRESENT: ARIEL HENRY Ariel Henry leads country as prime minister, with support from foreign powers. The Montana Accord, a civil society coalition, chooses Fritz Jean as interim president during a unitary summit, which Ariel Henry rejects.

SEPTEMBER 2021 -Gangs act as de facto authorities in parts of the country, including parts of the capital, controlling access to hospitals and markets, enforcing tight curfews and driving thousands from their homes.54 A gang truce is brokered to allow aid convoys to leave Port-au-Prince and reach August 2021 earthquake-hit areas.

OCTOBER 2021-G9 holds up fuel trucks at port, leading to fuel shortage in country, demanding Henry’s resignation. 400 Mawozo abduct 17 US missionaries, 56 prompting US to target the gang’s US arms suppliers and extradite its leader.

2022The criminal federalization of Port-au-Prince’s gangs means that most gangs in the capital now belong to either the G9 or G-Pep alliances; 400 Mawozo joins G-Pep.

January: When Henry visits Gonaïves, gangs attack his convoy.

Political event Regime/date Gangs, non-state armed groups, political violence Montana Accord calls for a provisional government to bolster security and ensure free elections in two years. Henry will remain in office, despite calls for him to step down by the Montana Group, leading to further instability in Haiti, including sporadic economic protests.

FEBRUARY APRIL–MAY Escalating gang violence as groups fight to control more territory amid the power vacuum.60 Fighting between late April and early May leaves at least 188 dead and displaces over 16 000 in Port-au-Prince.

JULY- Fifty die in clashes between G-Pep and G9 in Cité Soleil district of Port-au-Prince (a day after the first anniversary of the assassination of President Moïse).

Sources:

United Nations

Global Initiative

Radio France Inter

Jameson Francisque

Jhon Picard Byron, Université d’État d’Haïti (UEH)

Athena R. Kolbe, University of North Carolina